Scales and Rhythms

Rhythms

There has been little documentation of rhythms in northeast Africa, but I have done my best to gather what I have encountered in my own field research, recordings (both historical and contemporary), and work done by other researchers.

In contemporary Ethiopia, many musicians and listeners commonly associate certain rhythms with certain ethnic groups, and this musical multiculturalism is frequently presented in state-sponsored music performances and broadcasts. In everyday music-making, however, this is a bit more complicated: music and its makers are always on the move, so musical sounds and practices are commonly borrowed and shared. The agwaa-ga rhythm, for example, though associated with the Anywaa ethnic group, can also be found in some Nuer recordings. So, although many of these rhythms are labelled according to region or ethnic group, be aware that these boundaries are certainly neither strict nor timeless.

Agwaa-ga

The agwaa-ga rhythm, practiced in Anywaa music, accompanies the song genre of the same name. The agwaa-ga has been around a while: Osterlund (1978) documented it during his field research with the Anywaa in the 1970s, and the drumming on these recordings is almost identical to what we still hear today.

The agwaa-ga requires three drums of different sizes (read more about musical instruments here) to be performed. This particular recording was made in the Mekane Yesus Anywaa Church in Gambella wereda, where Ojho and Apay demonstrate.

Dudi møa thero

Another rhythm of the Anwyaa is the dudi møa thero. "Dudi møa thero" translates approximately to "small song," which is contrasted with "dudi møa døngø" ("big song.") "Big songs" include traditional genres such as agwaa-ga and obeerø, while "small song" encompasses songs composed outside of these frameworks and translations of Western hymns. This rhythm is quite common in the Anywaa church.

Especially in the villages, Anywaa engage in drumming and other forms of music-making quite young. This following video was recorded impromptu in the village, Gok, and these children do a pretty good job of playing dudi møa thero:

Gonder (Amhara)

This rhythm is very popular in Ethiopia and is especially identified with Gonder (may also be spelled "Gondar"; in Amharic, "ጎንደር") in the Amhara region of northern Ethiopia. It is in a very fast 3/8.

The following music video, by Emebet Negasi, features this rhythm and is actually filmed on-site in the city of Gonder, which boasts some notable architecture dating back to the 17th century during the time of Emperor Fasilidades, who founded the city as the capital of his empire at the time.

Gurage

Gurage is a zone in Ethiopia's Southern Nation, Nationalities, and People's Region (often abbreviated SNNPR). It is also the name of an ethnic group, many of whom live in this zone. The drummer plays a quarter note rhythm while the dancers and singers clap eighth notes.

Hadiya

Hadiya (also spelled Hadiyya) refers to both a zone and an ethno-linguistic group in Ethiopia's Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region. The following videos were recorded at the Hadiya Cultural Center in Hosaena in 2015, where the Hadiya Cultural Troupe was gracious enough to demonstrate some of their commonly-used rhythms, dances, and songs.

Bekelech Biruk demonstrates one of the drumming techniques in the following video.

This next video shows the drumming in the context of song and dance. According to members of Hadiya Cultural Troupe, this song ("Uweye") is sung by Hadiya women as they go home from the market. The lyrics compliment and express appreciation for one another.

Obeerø

The obeerø is another rhythm commonly used in Anywaa music, associated with the song genre of the same name. Ojho demonstrates at the Mekane Yesus Church in Gambella wereda in July 2016.

Shewa (Oromo)

This rhythm was described to me as belonging to the Oromo of Shewa region in central Ethiopia. I heard it accompanying several performances of Oromo songs in Addis Ababa, and it can also be heard in studio-produced music. The synth drum on this particular music video makes it easy to hear.

Tigrigna

The Tigrigna rhythm (also spelled "Tigrinya" or ትግርኛ) is associated with the ethno-linguistic Tigrayan people, who mainly hail from northern Ethiopia's Tigray region and Eritrea. This rhythm is nearly ubiquitous in Tigrigna music, usually played on the 2-headed drum or pre-programmed into a keyboard.

Scales

There's some debate on exactly how many different scales there are in Ethiopia and their tuning. There are many regional variations, and many performers have flexible concepts of pitch. In the 20th century, with the urbanization of Ethiopian music traditions and the establishment of traditional orchestras, musicians in Addis Ababa have made some efforts to consolidate a standardized set of pentatonic scales. More recently, use of technologies such as the keyboard and autotune has also facilitated an increase in the use of equal-tempered tuning in studio-produced music.

Most Ethiopian teachers, scholars, and urban musicians agree that there are at least four scales practiced in Ethiopia: tizita (ትዝታ), bati (ባቲ), ambassel (አምባሰል), and anchihoye (ኣንቺሆዬ). Collectively, these scales are known as k'ignit (ቅኝት).

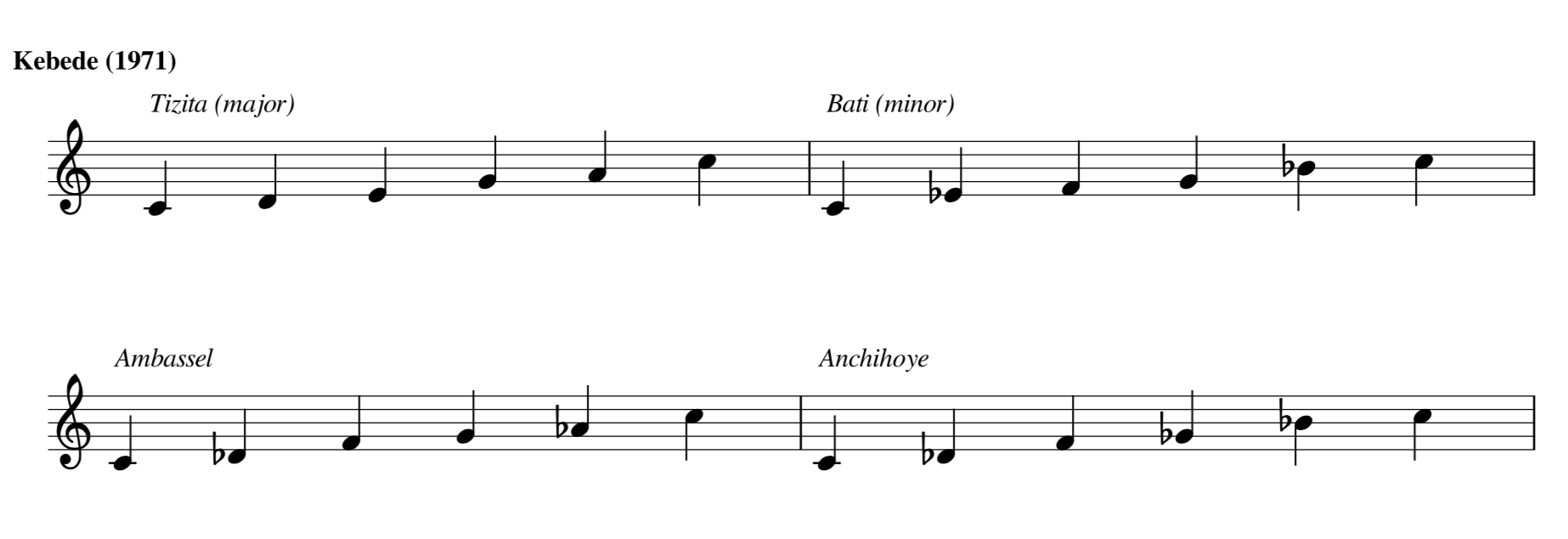

Late Ethiopian ethnomusicologist Ashenafi Kebede notated these four scales as follows:

This approximately matches what Alemayehu Fanta, traditional musician/singer and teacher at Addis Ababa University Yared School of Music, demonstrated to me on the masink'o (in Amharic, ማሲንቆ, the Ethiopian one-stringed fiddle) and krar (in Amharic, ክራር, a five-six stringed pentatonic lyre). However, it's important to note that these transcriptions don't really reflect the tuning, since a lot of music played on traditional instruments is not equal-tempered.

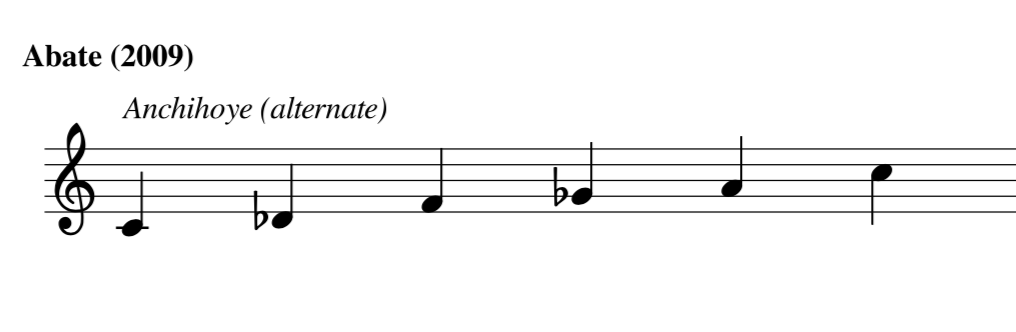

Since Ethiopian scales don't fit neatly into Western equal-tempered scales, there are some alternate ways of transcribing some of them. Abate (2009), in fact, transcribes anchihoye differently from Kebede.

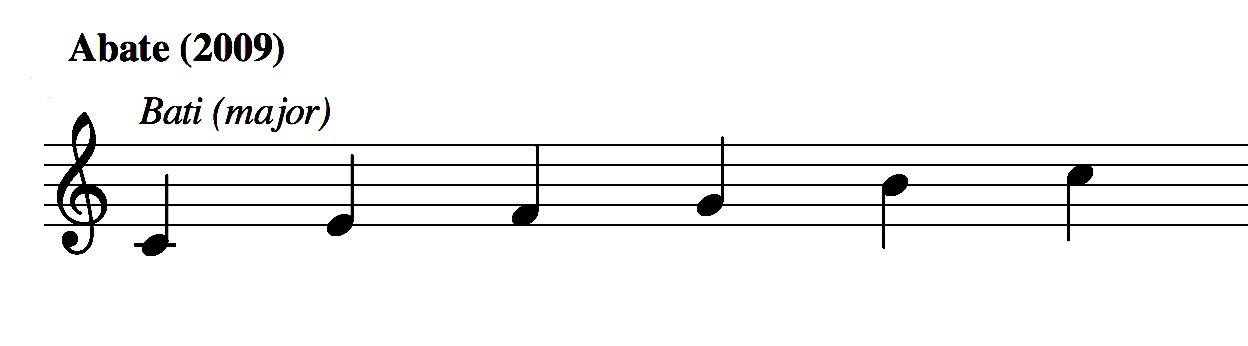

There is also some variation in the notation of bati, and Abate (2009) proposes that there is also a "major" version of it:

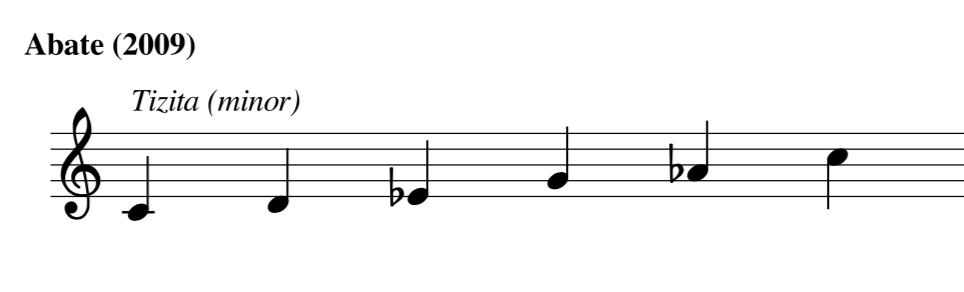

Abate (2009) and some Addis Ababa musicians also recognize a variant of tizita, tizita minor.

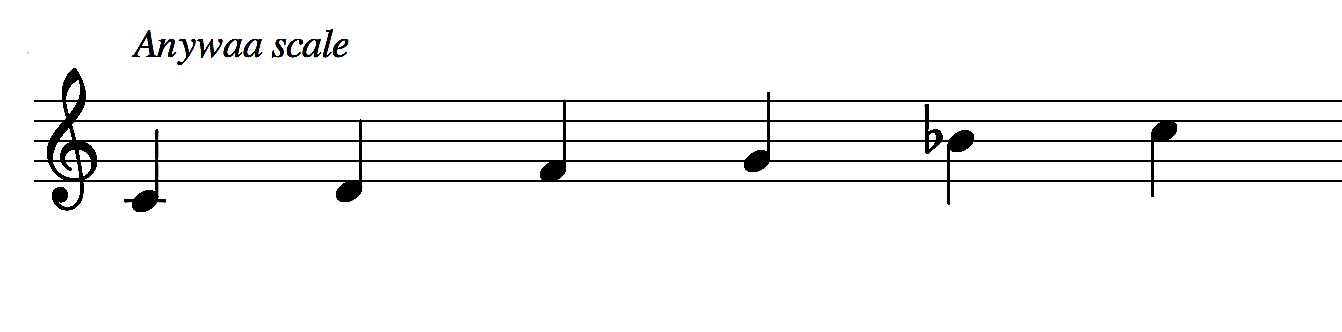

These k'ignit are largely derived from the Amhara region, but some version of anhemitonic penatonic scales (including tizita major and bati minor) are present in other regions, including Gambella, where I have done the bulk of my field research. There is another particular anhemitonic scale that I have heard in several Anywaa songs, including "Jwøk aa" that uses the second scale degree of tizita major as its "tonic" note.

Abate (2009) has documented additional scales throughout Ethiopia, but the reductive nature of Western musical notation makes it difficult to ascertain how closely these resemble actual musical practice. It is also uncertain to what extent these additional scales are self-consciously articulated by practicing musicians in their respective regions. In my own research in Addis Ababa, musicians have only referenced the four main k'ignit, plus tizita minor.

Ultimately, one can better understand these scales when hearing them rather than viewing them in notation. The YOD Abyssinia Cultural Band (featuring Yahalem Zod Negussie on krar, Baynesagn Birhani on masinqo, Tewodros Bogale on washint, Zeriyun Girma on drums, and directed by Adugna Chekol) in Addis Ababa demonstrate tizita, tizita minor, bati, ambassel, and anchihoye in the following series of melodies:

Credits and Bibliography

Abate, Ezra. 2009. “Ethiopian Kiñit (Scales): Analysis of the Formation and Structure of the Ethiopian Scale System.” In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, edited by Svein Ege, Harald Aspen, Birhanu Teferra, and Shiferaw Bekele, 1213–24. Trondheim.

Kebede, Ashenafi. 1971. “The Music of Ethiopia: Its Development and Cultural Setting.” Dissertation, Wesleyan University.

Osterlund, David Conrad. 1978. “The Anuak Tribe of South Western Ethiopia: A Study of Its Music within the Context of Its Socio-Cultural Setting.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Weisser, Stéphanie, and Francis Falceto. 2013. “Investigating Qәñәt in Amhara Secular Music: An Acoustic and Historical Study.” Annales d’Éthiopie 28 (1): 299–322.

Weisser, Stéphanie, and Didier Demolin. 2013. “Variability as a Key Concept: When Different Is the Same (and Vice Versa).” In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Folk Music Analysis, edited by P. Van Kranenburg, C. Anagnostopoulou, and A. Volk, 21–27. Amsterdam: Meertens Institute.